Multilingual Training Drives Engagement, Productivity, Motivation, Best-practice Adherence, Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Retention and Security Compliance Across Your Organization

Language and Learning in Global Workplaces

Today's organisations are often global, either physically or remotely, and employees must often learn new skills in a language that is not their native tongue. As companies undergo digital transformation and roll out training programmes worldwide, language gaps emerge – for example, an upskilling course may be delivered in English to a workforce where many employees are non-native English speakers. This scenario is increasingly common; surveys indicate that almost one-third of employees are non-native speakers of their organisation's primary language. While adopting a common corporate language can streamline communication, it also introduces challenges for learning, knowledge transfer and retention. Research shows that working or learning in a second language can increase cognitive load, hinder knowledge sharing, and even impact job performance. In the following paragraphs, we will examine how learning in a non-native language affects cognitive load, knowledge retention, knowledge transfer, and productivity in workplace training and upskilling..

Cognitive Load and Knowledge Retention in a Second Language

Learning new concepts in a foreign language imposes an extra cognitive burden on the learner. Instead of directly processing the material, the learner must also mentally translate or interpret the language, which consumes working memory capacity. According to cognitive load theory, this additional "translation" task is an extraneous cognitive load that can reduce the brain's ability to absorb and retain new knowledge. Experimental research confirms that learning content in one's native language yields better comprehension and retention than learning the same content in a second language.

For instance, in a set of controlled experiments, French students were asked to learn from texts about academic subjects in either French (their L1), English/German (L2 only), or L2 with native-language support. The results showed that students learned the material best in their native language, followed by the bilingual support condition, whilst those who attempted to learn entirely in the foreign language had the worst gains in content knowledge. The authors note that "immersing students in a foreign language in order to learn content resulted in the worst gains in content learning", likely because attempting to learn complex material in a second language incurs a cognitive load penalty. In other words, a significant portion of mental effort is diverted to decoding the language rather than understanding the content, leaving fewer cognitive resources to form long-term memories of the material.

Learning in a non-native language can also reduce the depth of processing of information. Psychologists have found that using a foreign language tends to diminish the vividness of mental imagery and visualisation. When people think or learn in their second language, they may not engage the same rich mental pictures or intuitive associations that they would in their first language. Researchers at the University of Chicago observed that participants using a foreign language reported less vivid sensory imagery than those using their native language, suggesting that the brain's capacity to create mental models is somewhat blunted in L2.

This phenomenon (sometimes called the "foreign language effect") can make learning less intuitive and more abstract, potentially impairing comprehension and memory. Indeed, if learners must translate instructions and concepts internally – "understand the foreign language, translate it to their native language and then store the details" – the process can become "tedious" and mentally draining. As a result, knowledge retention suffers; learners might struggle to recall training content taught in a second language as clearly or accurately as content learned in their first language.

In sum, cognitive science findings indicate that learning in a non-native language increases mental workload and can reduce the efficiency of learning and memory. Designers of corporate training should be mindful that an employee taking a course in an unfamiliar language is effectively doing double the work – learning the content and the language – which can slow down mastery and require additional reinforcement to achieve the same retention levels as native-language instruction.

Knowledge Transfer and Communication Barriers in Organisations

Language differences don't only affect individual learning – they also have a profound impact on knowledge transfer and communication within organisations. In multilingual companies, employees with limited proficiency in the company's working language often participate less in discussions, ask fewer questions, or avoid complex dialogues. A qualitative study in the Journal of World Business found that "evident language barriers (lack of lexical and syntactical proficiency) reduce participation in team communication", which in turn impedes knowledge processing activities in multinational teams. When some team members are not comfortable expressing themselves in the training or meeting language, important knowledge may not be shared, and both "basic and sophisticated knowledge processing activities" suffer.

In other words, teams might get by on superficial communication, but deeper knowledge exchange (brainstorming, problem-solving, innovating) is disrupted if members cannot fully contribute linguistically. The same study also highlighted "hidden language barriers" – more subtle issues like differences in communication style or tone when using a second language – which can impair sense-making and mutual understanding. For example, a literal translation of an idea from one's first language might come across oddly in another language, or speakers might miss nuanced meanings. These hidden barriers erode trust and clarity, further disrupting complex knowledge work.

Real-world surveys and reports reinforce just how much language barriers can hamper knowledge transfer and productivity. Some striking findings include:

-

Reduced Knowledge Sharing: In one global survey of HR leaders, around 75% of employees with low English proficiency were found to have limited participation in workplace training and fewer opportunities for promotion compared to those fluent in the company's main language. This indicates a vicious cycle where language gaps limit involvement in learning (and thus skill acquisition), which then stalls career growth and motivation. Another study of global teams observed that uneven language fluency sparked feelings of apprehension and exclusion – non-native speakers felt anxiety about speaking up, whilst native speakers felt left out when others resorted to their native tongue – creating "a cycle of negative emotion" that disrupted collaboration and information exchange on the team. Such emotional turmoil can further reduce employees' willingness to engage in knowledge sharing.

-

Productivity and Error Risks:

Simply put, when teams cannot communicate effectively due to language mismatches, productivity suffers and errors can increase. As one industry report succinctly stated: "What happens when teams can't communicate effectively? Productivity suffers, collaboration becomes impossible, and employees grow increasingly dissatisfied." In high-stakes environments like manufacturing or safety, miscommunication can even be dangerous. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration estimates that language barriers contribute to 25% of job-related accidents, a sobering statistic highlighting the practical risks when instructions or knowledge are misunderstood.

Even in office settings, the cost of misunderstandings is high – companies can lose up to £1.8 million per year due to language barriers, according to research by Common Sense Advisory, stemming from errors, inefficiencies, and lost business. They also found that as much as 60% of cross-border business deals fail or underperform due in part to language and cultural barriers. These figures make clear that poor knowledge transfer across language divides isn't just a minor inconvenience; it directly impacts the bottom line. Valuable training knowledge may never be applied if employees can't fully grasp it, and corporate initiatives can flounder if key concepts "get lost in translation".

-

Slower Diffusion of Best Practices:

In multinational organisations, language friction can slow down the spread of new ideas and best practices from one location to another. A field study of automotive firms noted that plants with higher language barriers to the foreign head office scored lower on management quality metrics. The implication is that when local managers struggle to communicate with experts or leadership due to language, they absorb fewer best practices.

Another recent study by Guillouet et al. (2021) provides direct evidence that language barriers hinder management knowledge transfer within multinationals, especially from expatriate managers to local staff. Communication in English (a common corporate lingua franca) was examined in a developing-country context: they found that when domestic managers are not fluent, they interact less with foreign experts, missing out on tacit knowledge and mentorship. Over time, this leads to lower adoption of efficient processes and depresses team performance.

In summary, numerous studies converge on the finding that language gaps act as a drag on organisational learning – knowledge doesn't flow freely, and employees cannot fully capitalise on training and development opportunities if they are delivered in an unfamiliar language.

Productivity Outcomes in Training and Upskilling Programs

The ultimate concern for organisations is how these language-related challenges translate into training effectiveness and workplace productivity. When employees struggle to learn due to language difficulties, training programmes may yield less benefit – workers might take longer to become competent, or fail to retain key knowledge, leading to lower productivity on the job. However, research also shows that when organisations invest in overcoming language barriers, the payoff can be significant in terms of performance outcomes.

A powerful example comes from a randomised controlled trial conducted in Myanmar within a multinational company. In this experiment, local mid-level managers who spoke Burmese were given intensive English-language training to improve communication with their English-speaking foreign managers (expatriates from headquarters). The impact on productivity was measured by simulating management tasks. The results were striking: teams led by managers who received language training performed a task 15% faster, on average, with no loss in accuracy, compared to teams with untrained (lower-English) managers.

In the simulation, production teams managed by the English-trained group completed the work significantly quicker (0.19 minutes faster on a baseline of 1.28 minutes) – a sizable productivity gain – "so quality-adjusted productivity improved" because error rates remained the same. Why did productivity jump? The study found a clear mechanism: the managers with better English engaged in more frequent and more meaningful communication with their foreign supervisors, asking more questions per session and spending more time clarifying instructions. With clearer understanding, they could guide their teams more effectively and prevent mistakes before they happened. This field experiment elegantly demonstrates that reducing the cognitive and linguistic barriers in training (in this case via language upskilling) directly improved knowledge transfer and had measurable productivity benefits on operational tasks. In effect, giving employees the language tools to fully absorb training unlocked real performance gains on the factory floor.

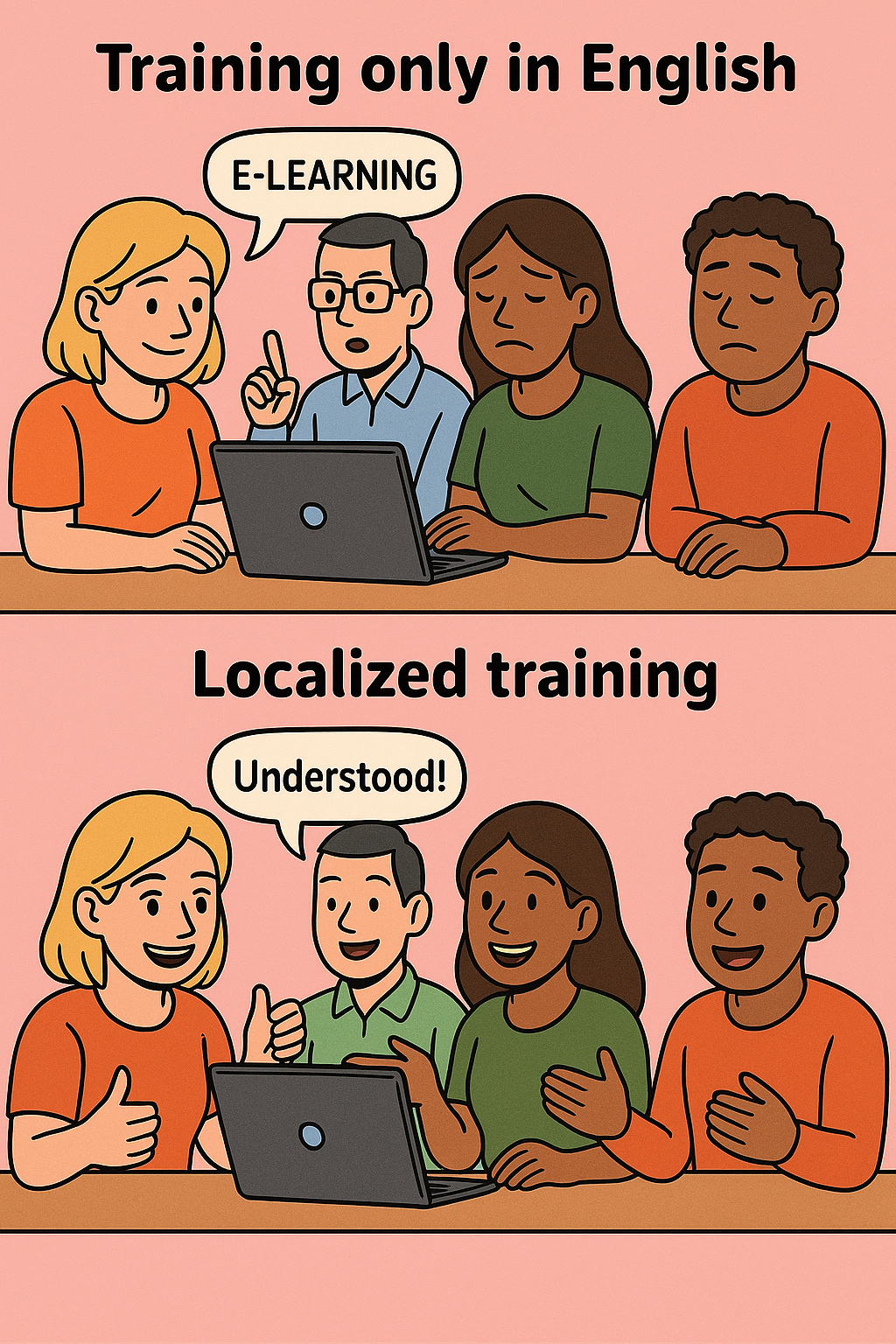

Beyond experimental evidence, companies themselves report positive outcomes from addressing language needs in training. Many organisations are now adopting bilingual training materials, translation of e-learning modules, or corporate language classes as part of their upskilling strategy. Learning programmes delivered in employees' native languages (or supported by translation) are shown to yield better understanding and "knowledge absorption", enabling staff to apply new skills faster. Conversely, if no accommodation is made for language differences, training programmes may not reach their full potential – as one training industry report put it, "There is no point in creating informative courses that can't be understood by the target audience". In practice, companies have found that localising training content (through translation and cultural adaptation) can boost learner engagement and reduce the drop-off rate in e-learning courses.

It's also worth noting the link between language-inclusive learning and employee retention and morale. If workers feel left behind because training is delivered in a language they struggle with, it can breed frustration. Surveys show that lack of growth and training is a top reason employees consider leaving (after salary) – and if language proficiency is a hidden gatekeeper to advancement, it can create resentment. On the other hand, providing language support signals an inclusive learning culture, empowering upskilling and career progression.

In short, investing in language is increasingly seen as part and parcel of workforce development. McKinsey Global Institute has estimated that widespread upskilling and reskilling (across all sectors and regions) could add £5.1 trillion to global GDP by 2030 – but to achieve this, organisations must ensure these training initiatives are accessible to employees of all language backgrounds. Otherwise, a significant portion of the workforce might not fully realise their new skills, resulting in uneven productivity gains.

.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways for Organisations

Learning in a second language poses significant challenges that can reduce training effectiveness and organisational productivity, but these challenges are increasingly well-understood and can be mitigated. Increased cognitive load is one major factor – when employees must learn new material in a non-native tongue, their working memory is taxed, often leading to lower comprehension and retention of that material.

At the organisational level, language barriers impede knowledge transfer: workers with limited proficiency may shy away from discussions or misunderstand key concepts, causing critical know-how to remain siloed or poorly implemented. The net effect can be seen in reduced productivity, more mistakes, and even financial losses due to miscommunications.

However, research also offers a hopeful message – by acknowledging and actively addressing language differences (through translated learning content, bilingual instruction, or language training), companies can dramatically improve knowledge uptake and on-the-job performance. The case of a 15% productivity boost after language-focused training intervention is a vivid illustration.

In an era of digital transformation, where continuous learning is essential, organisations would do well to integrate language support into their upskilling programmes. This not only enhances knowledge retention and skill transfer, but also fosters an inclusive environment where all employees can contribute to their full potential. The evidence is clear that bridging language gaps is more than a cultural nicety – it is a smart strategy to amplify the impact of learning, drive productivity gains, and ensure no one is left behind in the knowledge economy.

Localise your e-learning

Europe-focused localisation expertise you can trust

Sources:

-

Tenzer, H., Pudelko, M., & Zellmer-Bruhn, M. (2021). “The impact of language barriers on knowledge processing in multinational teams.” Journal of World Business, 56(2).

-

Guillouet, L., Khandelwal, A., & Macchiavello, R. (2021). “Language Barriers in Multinationals and Knowledge Transfers.”

-

Roussel, S., et al. (2017). “Learning Subject Content Through a Foreign Language Should Not Ignore Human Cognitive Architecture: a Cognitive Load Theory approach.” Learning and Instruction, 52, 69–79.

-

Hayakawa, S. & Keysar, B. (2018). “Using a foreign language reduces mental imagery.” Cognition, 173, 8–15.

-

EF Education First (2024). Driving Talent Retention and Development through Language Learning.

-

Common Sense Advisory (2023). “The future of work: A shift towards soft skills and constant upskilling.”

-

Neeley, T., Hinds, P., et al. (Neeley & Hinds 2017). Research on lingua franca use in global teams.

-

Babbel for Business (2025). “How Language Barriers Affect Safety in the Workplace.” (OSHA estimate that 25% of job accidents involve language issues)